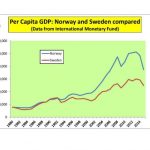

Worse off out? A graph showing why OECD and the Treasury are wrong

Oh dear, Brexit is going to mean economic armageddon. This was the message from George Osborne following the publication of a report from the Treasury, which looked at three possible exit scenarios. Now the OECD has weighed in with the same gloomy message, although its analysis is based on a worst case scenario.

These reports are all speculative – attempting to look into the future. Just supposing we had a case study of a situation covering a period in the past for which definitive figures were available.

Just suppose that there were two similar countries with similar climates and similar populations. Suppose that both spent similar sums on their welfare sysytems and both ran strongly export-driven economies but one was a member of the EU while one was a member of EFTA with full acccess to the EU’s single market via the European Economic Area agreement. This would provide us with a far better case study as to the likely financial implications of withdrawal rather than crystal ball gazing.

According to the Treasury, the non-EU member ought to be worse off but reality is actually very different. The graph above takes the per capita inflation-adjusted GDP figures for Norway and Sweden in US dollars from 1980 onwards. Up to 1995, the two countries enjoyed very similar standards of living. However, after 1995, when Sweden joined the EU, Norway powered ahead and the differential has persisted to the present day, even though production of Norway’s principal export, oil, peaked over a decade ago and oil prices have fallen in the past year.

It is true that a Canadian-style trade deal may not do much good to the economy, but it wouldn’t be possible to negotiate a free trade deal on these lines under the Article 50 timescale anyway. Using the only feasible exit route – in other words, taking Norway as an off-the-peg proven model, the evidence, as opposed to the Treasury’s forecast, suggests that we will most certainly not be worse off at all.

Further support for our belief that the UK would not be worse off come from Hugo van Randwyck’s analysis of past events when the UK took a step back from integration with the EU.

Take the period following our ejection from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992. Although 16th September is popularly known as Black Wednesday, it marked the beginning of a sustained economic recovery. Freed from the need to shadow the Deutschemark, interest rates could be reduced and unemployment began to fall. Compare the average price of a house in 1996 (£56.000) with today’s crazy prices.

He also pointed out that in the 1960s as member of EFTA, UK unemployment stood at around 2%. With far less pressure on housing due to much lower levels of immigration compared with today, only one breadwinner per household was needed to support the raising of a family and paying the mortgage.

Society and the economy has changes greatly since then, but claims that detaching ourselves from the EU wil damage our economy stand in sharp contrast to evidence from the past – both in this country and abroad. A badly-implemented exit would hurt business, but EEA/EFTA is a safe, proven alternative that will get us through the Brexit door.